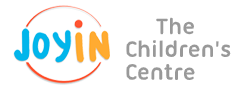

How Circular Reasoning Creeps Into Diagnoses of Developmental Disorders

Circular reasoning is a common logical error where the explanation for something simply restates the claim without adding new information. It’s like running in a circle—you never actually move forward.

In psychology and psychiatry, circular reasoning often sounds like this:

- “Why does he have ADHD? Because he can’t focus.”

- “Why can’t he focus? Because he has ADHD.”

Or:

- “How do we know this child has autism? Because they show certain symptoms.”

- “Why do they show these symptoms? Because they have autism.”

This pattern can apply to many developmental disorders, such as ADHD, autism, or sensory processing disorder. It offers no real insight into the child’s behavior—just a loop that sounds like an explanation but isn’t.

Diagnoses Are Descriptions, Not Causes

Diagnoses like ADHD or autism don’t cause behavior; they describe it. These terms are what we call “summary labels,” agreed upon by professionals to organize and communicate observed patterns of behavior.

For example:

- ADHD stands for hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder refers to challenges in social interaction and stereotyped behaviors.

Saying social difficulties are caused by autism is like saying autism causes autism—it’s meaningless. Diagnoses summarize symptoms but don’t explain why they occur.

As psychiatrist Allen Frances, who led the DSM-IV committee, stated:

“Mental disorders are constructs, not diseases. Descriptive, not explanatory.”

How Widespread Is This Error?

While most psychologists and psychiatrists understand this distinction, circular reasoning often permeates conversations among therapists, teachers, and parents. Many mistakenly believe that a diagnosis identifies a physical or biological “thing” in the brain that explains the behavior.

Professionals use tools like questionnaires and assessments to observe symptoms, not to uncover a specific biological cause. Yet, the public often interprets a diagnosis as evidence of an underlying “thing” that exists in the brain or nervous system.

The Confusion Between Medical and Psychiatric Diagnoses

This misunderstanding arises because people confuse how medical and psychiatric diagnoses work.

- In medicine, a diagnosis often identifies an underlying biological cause. For example, fever is a symptom, while the diagnosis (e.g., malaria, influenza) pinpoints the biological condition causing it.

- In psychiatry, diagnoses are descriptive—they categorize behaviors and symptoms but don’t identify a biological or neurological cause. Unfortunately, this distinction isn’t always clear to parents or therapists, leading to confusion.

What Really Causes Developmental Disorders?

To understand developmental disorders, we must move beyond the idea that diagnoses are causes. Behavior—whether functional or dysfunctional—emerges from a complex interaction of multiple factors, such as genetics, neurobiology, psychological development, life experiences, and interpersonal relationships.

While genetics and biology undoubtedly influence behavior, they constantly interact with a child’s environment and experiences, shaping outcomes in complex and dynamic ways.

Conclusion: The Role and Power of Relationships in Therapy

By rejecting a purely biological model, we can uncover the true potential of early intervention.

Every behavior reflects the interaction between a child’s unique neurological makeup and their environment. As therapists or parents, our primary responsibility is to use the relational context—the real-time, moment-by-moment interactions between us and the child—to create transformative experiences that foster development and learning.

Reference

Shedler J. A psychiatric diagnosis is not a disease. Psychology Today. Updated May 17, 2024. Accessed November 29, 2024.

Ahn WK, Flanagan EH, Marsh JK, Sanislow CA. Beliefs about essences and the reality of mental disorders. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(9):759-766.

Timimi S. A Straight Talking Introduction to Children’s Mental Health Problems (2nd ed.). Published August 20, 2013.