Up to 10% of all children have not yet begun using meaningful words by the time they reach their second birthday. Naturally, when a child does not talk at 2 years old, this can be source of great concern for parents.

Although, the majority of late-talking children acquire typical language at a later age with no long-term adverse

consequences, no words at 2 years may indicate a variety of developmental disorders, such as autism, intellectual disabilities, hearing loss, speech disorder, language disorders, or social communication disorder.

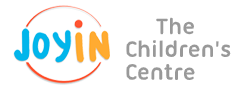

When a child is referred by parents for assessment, the challenge for the clinician is to understand what the late talking can mean and what intervention, if any, is needed.

Nonverbal interaction with parents and others, ability to engage in developmentally appropriate play and to understand words and multiple steps instructions, range and frequency of vocalization, presence of behavioral inflexibility are all key indicators that the clinician will have to carefully consider in forming the diagnosis.

An accurate, early, diagnosis can avoid the danger of the “wait and see” approach, that can waste precious time when a child requires clinical intervention and can guide parents into the right treatment choice for their child.

On the other hand an inaccurate diagnosis risks to lead parents into ineffective or even harmful interventions. A child, improperly diagnosed as having ASD, may be treated with intensive DTT (discreate trial training) and extrinsic rewards that could further hamper social development in late-talking children. Blowing whistles, electric toothbrushing, and oral massages may be unnecessarily prescribed to strengthen and stimulate the tongue and the oral muscles under the false assumption of a oral structure defect. Or, brushing of a child’s arm, weighted vest, or physical activities may be recommended to a child improperly diagnosed with “Sensory Integration Disorder”.

A correct diagnosis opens the possibility of targeted intervention. There is no one-size-fits-all treatment for late-talking children: Nutrition, attachment, emotional regulation, type and quality of social interaction are just few of the areas where intervention may be required. However, in every case it is also critical to support the child’s social development by strengthening nonverbal communication and social engagement. Depending on the case this may be done through direct intervention with the child by a trained therapist or through parent-mediated intervention. In any case the final goal is to establish the natural social conditions that can allow the child to develop language without special support.

References:

Late-talking children: A symptom or a stage?, Camarata S. (2014), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

What does it mean when a child talks late?, Camarata, S. (2014). The Brown University Child and Adolescent Behavior Letter, 30(12), 1–7.